- The Mystery of the Mary Celeste: The Enduring Legend of the Ghost Ship

- Part 1: The Silent Hull Drifting in the Atlantic – Overview of the Incident and Discovery

- Part 2: The Mary Celeste, Her Ship and Crew – Background to the Departure and Personalities

- Part 3: The Beginning of Suspicion and Investigation – The Gibraltar Salvage Court Hearing and Initial Conclusions

- Part 5: Major Theories and Their Examination Surrounding the Incident

- Part 6: Factors Deepening the Mystery and the Incident’s Cultural Impact

- Part 7: Re-evaluation and New Perspectives in the Modern Era – Scientific Considerations and Erosion of Evidence

- Part 8: The Unconcluded Mystery, and Why It Endures

The Mystery of the Mary Celeste: The Enduring Legend of the Ghost Ship

The name “Mary Celeste” is etched into the depths of the Atlantic Ocean. For many, this ship evokes the story of the most inexplicable ghost ship in history, whose crew vanished without a trace. When discovered, the vessel was intact, its cargo untouched, and with ample food and water remaining – yet, inexplicably, all human life had disappeared. This peculiar incident, since its occurrence in 1872, has captivated imaginations worldwide for over 150 years, becoming a timeless maritime mystery.

Part 1: The Silent Hull Drifting in the Atlantic – Overview of the Incident and Discovery

On December 5, 1872, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, humanity witnessed one of the most bizarre sights in maritime history. On that day, the American brigantine “Dei Gratia” was en route from New York to Genoa, Italy. Approximately 600 miles southeast (about 965 kilometers) between the Azores and Portugal, at latitude 38°20′N, longitude 17°15′W, Captain David Morehouse Johnson, commanding the Dei Gratia, spotted a brigantine behaving strangely.

A Strange Encounter and Ominous Signs

Captain Johnson, a seasoned and experienced mariner, first noticed that the ship was not signaling distress, yet was navigating in an unusually erratic manner. Some of its sails appeared damaged, but more unsettling was the distinct lack of any crew at the helm. Under the midday sun, the ship drifted like a phantom, seemingly at the mercy of the wind.

Peering through his binoculars, Captain Johnson was astonished. The ship was the familiar “Mary Celeste.” He had previously met the Mary Celeste and its captain, Benjamin Spooner Briggs, at a New York pier, and the two captains were said to be friends. Witnessing a familiar vessel in such an abnormal drifting state, Captain Johnson immediately sensed danger. Convinced that a major emergency had occurred, he ordered his first mate, Oliver Devoe Morehouse, and several crew members (John Wright, Abel Fosdick, Boswell Haynes) to lower a rescue boat and board the Mary Celeste.

Onboard Investigation: A World Frozen in Time

When First Mate Morehouse and his team boarded the Mary Celeste, they were met with an eerie silence. On the deck, which swayed with the Atlantic waves, some ropes were scattered and sails were damaged, but overall, the hull remained in a navigable condition. The cargo of industrial alcohol barrels was securely fastened, with no signs of shifting. Yet, nowhere could a single crew member be found.

Morehouse meticulously searched every corner of the ship.

- On Deck:

- Main Hatch Open: The main hatch, which would normally be securely closed during voyages or rough weather, was found open. This suggests either a hasty departure or an ongoing loading/unloading operation.

- Missing Lifeboat: It was discovered that one of the ship’s lifeboats was missing from its stern davits. This was the strongest evidence suggesting the crew had voluntarily abandoned the ship. However, if so, why they left without sufficient food or water, and why they didn’t send out a clear distress signal, raised new questions.

- Sail Damage: Some sails were damaged, and the rigging was in disarray, but this could be attributed to a typical storm and did not conclusively indicate an anomaly.

- Living Quarters and Captain’s Cabin:

- Unfinished Logbook: In Captain Briggs’ cabin, the ship’s logbook lay neatly on his desk. The last entry was dated November 25, 1872, about 10 days before the discovery, with subsequent pages blank. The log contained no unusual weather or event records, noting only that the ship was sailing about 100 miles west of Santa Maria Island in the Azores. It was as if something had suddenly forced the captain to stop writing mid-sentence.

- Personal Belongings Remaining: The captain’s sextant (navigational instrument) and watch were left behind, as were the crew’s personal items such as clothes, pipes, playing cards, personal letters, and even Sarah Briggs’ (the captain’s wife) sewing machine and piano, and Sophia’s (the daughter’s) toys. Valuables, including personal effects, remained untouched. This completely ruled out piracy and created a contradiction: if the crew left in a hurry, why didn’t they take their valuables?

- Meal in the Galley: In the galley, a meal was left cooking and utensils were scattered. The fire had gone out, but it gave the impression that something had happened in the midst of meal preparation, causing everyone to leave in haste, leaving strong traces of daily life.

- Cargo Hold:

- Untouched Cargo: The Mary Celeste’s cargo, bound for Genoa, Italy, consisted of 1,700 barrels (approximately 9,800 liters) of denatured alcohol. This was primarily industrial alcohol, highly volatile and flammable. However, all barrels were intact and securely fastened, with no signs of leakage. There was no evidence of plunder, and the cargo hold was orderly.

- Other Anomalies:

- Bow Damage: On the ship’s bow, there was a 3-meter long rope (cordage) that appeared to have been cut by a sharp blade. It was unclear whether this damage was accidental or intentional.

- Misaligned Compass: The navigator’s compass was slightly off. This might suggest a violent jolt or collision, but it was difficult to connect with other evidence.

- Missing Navigational Instruments: The chronometer (high-precision clock) and sextant, essential for determining the ship’s exact position, were also missing. This suggested that the crew, if abandoning ship, had taken at least the minimum necessary navigational tools with them.

These numerous peculiar clues suggested a scenario far more complex than a simple maritime accident. The sight of a deserted ship, silently drifting across the Atlantic, marked the beginning of “The Mystery of the Mary Celeste.” Captain Johnson of the Dei Gratia decided to tow the Mary Celeste to Gibraltar, and this unprecedented event soon made headlines worldwide.

Part 2: The Mary Celeste, Her Ship and Crew – Background to the Departure and Personalities

The Mary Celeste was not just a mere cargo ship. Her hull, as if destined for a peculiar fate, underwent repeated name changes and renovations. And the crew who embarked on her final voyage were individuals with their own lives and stories.

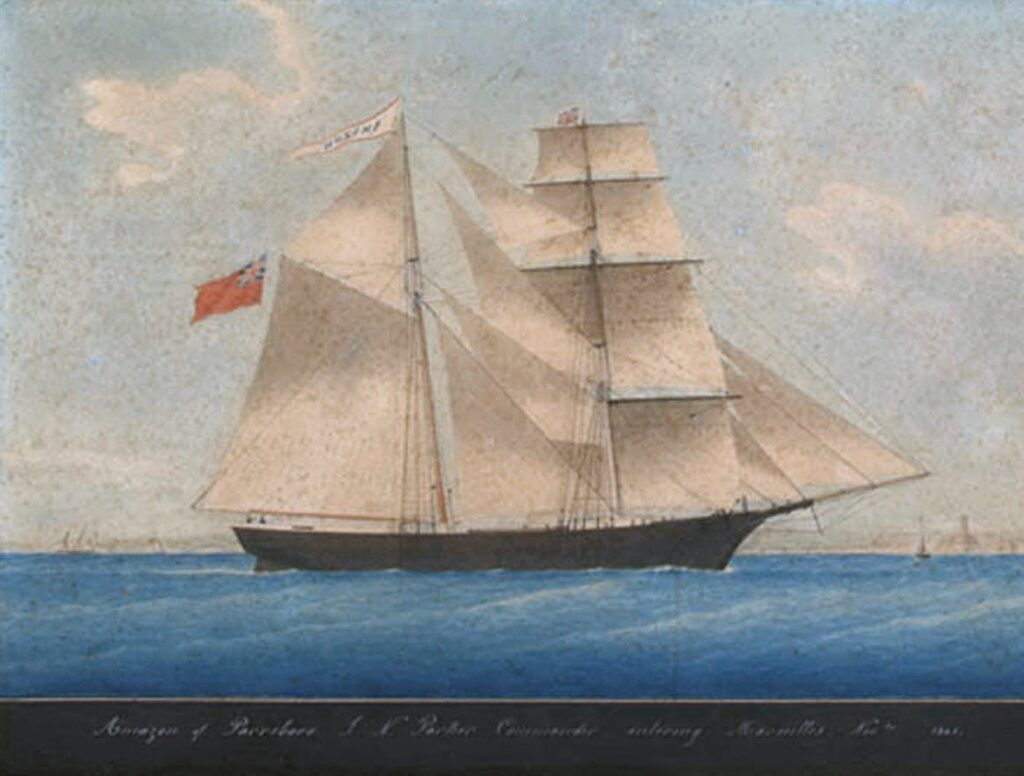

The Ship’s Birth and Unlucky Beginnings: The Era of the Amazon

The story of the Mary Celeste began in 1861 as the brigantine “Amazon,” built in Amherst, Nova Scotia, Canada. She was a medium-sized vessel, approximately 31 meters long and weighing about 282 gross tons. However, from her maiden voyage, she seemed to be cursed with misfortune. Her first captain, Robert MacLellan, fell ill during a voyage from New York to London and died in the Atlantic. Subsequently, the Amazon ran aground several times and collided with other ships, with some problem reportedly occurring on almost every voyage. Consequently, sailors began to whisper that she was an “unlucky ship.”

A New Beginning: Renaming and Refitting as the Mary Celeste

The ill-fated Amazon was purchased in 1867 by American businessman Richard W. Haynes and underwent extensive renovations in New York. Her hull was lengthened, and her structure reinforced. And, as if to break from her unfortunate past, her name was changed to “Mary Celeste.” This new name, evoking purity and hope, seemed to symbolize a new beginning for the ship. After the renovation, the ship was operated by several co-owners based in New York.

Captain Benjamin S. Briggs: A Trustworthy and Experienced Mariner

The last captain of the Mary Celeste was 37-year-old Benjamin S. Briggs. He was a devout Methodist from Wareham, Massachusetts, and came from a long line of seafarers. Known as a highly capable and trustworthy captain with many years of sailing experience, his reputation as a navigator was excellent. He was strict yet respected, and highly trusted by his crew. He disliked reckless behavior and always prioritized safety.

Captain Briggs cherished his family above all else and often brought his wife and young daughter along on voyages. His wife, Sarah Briggs, also loved the sea and wished to be with her husband.

The 10 Souls Who Embarked on the Final Voyage

The Mary Celeste’s voyage was no exception. Captain Briggs had his wife, Sarah Elizabeth Briggs (31 years old), and his beloved daughter, Sophia Matilda Briggs (2 years old), on board. In addition, there were eight crew members.

These 10 individuals were the last humans to set sail into the Atlantic with the Mary Celeste.

- Captain: Benjamin S. Briggs (37 years old) – An experienced and skilled captain.

- First Mate: Albert G. Richardson (28 years old) – A reliable young mate from New York.

- Second Mate: Andrew Gilling (25 years old) – Another experienced young mate.

- Cook and Steward: Edward W. Head (23 years old) – American.

- Four Seamen: All were German or Danish. Diverse crews were common on merchant ships at the time.

- Volkert Lorenzen (29 years old) – German.

- Arian Faunder (25 years old) – German.

- Asmus Andriessen (27 years old) – German.

- Boyse Lorenzen (23 years old) – German.

- Passengers:

- Sarah Elizabeth Briggs (31 years old) – The captain’s wife.

- Sophia Matilda Briggs (2 years old) – The captain’s daughter.

This crew, in addition to the captain’s family, consisted of veteran sailors and younger seamen, all described as steady and experienced. There was reportedly no one among them likely to cause trouble on board.

Departure from New York: November 7, 1872

On November 7, 1872, the Mary Celeste set sail from off Staten Island in New York Harbor into the Atlantic. Her destination was Genoa, Italy, and as mentioned, her cargo consisted of 1,700 barrels (approximately 9,800 liters) of denatured alcohol, valued at about $35,000 at the time. This alcohol was primarily used for industrial purposes (fuel, solvents, etc.) and was a highly flammable and dangerous substance.

The voyage initially appeared to proceed smoothly. According to the last logbook entry on November 25, about three weeks after departure, the Mary Celeste was sailing smoothly west of the Azores. A few days later, she coincidentally encountered the Dei Gratia, and Captains Johnson and Briggs exchanged greetings. At this point, there was no apparent anomaly with the Mary Celeste.

However, after this last encounter, the Mary Celeste suddenly vanished, only to be discovered later in an unprecedented state.

Part 3: The Beginning of Suspicion and Investigation – The Gibraltar Salvage Court Hearing and Initial Conclusions

After the Mary Celeste was towed to Gibraltar by the Dei Gratia, her inexplicable condition immediately drew significant attention. Gibraltar, a British territory, was an important maritime hub at the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea, where investigations into international maritime incidents were conducted. To investigate this extraordinary event, the British Vice Admiralty Court immediately commenced a salvage court hearing.

Purpose of the Hearing and Gibraltar’s Attention

The primary purpose of the hearing was to determine whether the Mary Celeste was in a condition to be considered “abandoned” by the Dei Gratia, and to decide the amount of salvage award to be paid to the Dei Gratia. However, as the incident was so unusual, the investigation extended beyond merely determining the salvage award to the greatest mystery: the disappearance of the crew.

Initially, various speculations spread among the people of Gibraltar and those involved in the hearing.

- Pirate attack? However, this theory quickly lost credibility as the valuables and cargo on board were untouched. It was highly unlikely for pirates to attack a ship without plundering anything.

- Mutiny or murder by the crew? Captain Briggs was a respected figure, and there was no evidence of problems with the crew. Furthermore, no signs of struggle, bloodstains, gunshots, or weapons were found on board.

- Encounter with a sea monster? While outlandish for the time, such strange conjectures were made due to the inexplicable nature of the event in the vast ocean.

- Insurance fraud? Suspicions also arose that the captain and owners might have conspired to abandon the ship for insurance money. However, given Captain Briggs’ character and the fact that the ship was found largely intact, this theory was quickly dismissed.

Rigorous Investigation and Solicitor General Solly-Flood’s Suspicions

The hearing was meticulously conducted under the direction of Frederick Solly-Flood, the Solicitor General of Gibraltar. Solly-Flood became deeply involved in the case and developed strong, personal views. From the outset, he harbored strong suspicions that the crew of the Dei Gratia had murdered the Mary Celeste’s crew and seized the ship.

The Mary Celeste was moored in Gibraltar harbor and subjected to a thorough inspection by experts.

- Hull Damage: A deep cut, about 3 meters long, was found on the ship’s bow planking, as if made by a sharp instrument. Solly-Flood claimed this was caused by an axe. Additionally, suspicious reddish stains were found on the ship’s bottom. Solly-Flood strongly insisted these were bloodstains and demanded a chemical analysis by a government analyst. However, the analysis concluded that they were not bloodstains, but rather rust, wood coloring, or wine stains.

- Mainmast Damage: Strange marks were also found at the base of the mainmast. Solly-Flood also interpreted these as indicative of violent acts.

- Pump Anomaly: The ship’s pump was found disassembled. This suggested the possibility that the ship had taken on water and they were trying to pump it out, but there was very little evidence of water ingress inside the ship.

Captain Johnson and First Mate Morehouse of the Dei Gratia testified multiple times, detailing the circumstances of the discovery. Their testimonies supported the fact that the ship was indeed in an “abandoned” state. However, Solicitor General Solly-Flood thoroughly doubted their testimonies, at times becoming emotional. He subjected the Dei Gratia’s crew to harsh interrogations, openly suggesting they had murdered the Mary Celeste’s crew and thrown their bodies overboard.

Solly-Flood insisted that “the ship was bloody” in an attempt to support his theory. However, objective evidence, especially the results of the chemical analysis, did not support his claims.

Conclusion of the Hearing and Remaining Questions

Ultimately, the Gibraltar hearing awarded the Dei Gratia a relatively small salvage fee of only one-sixth of the Mary Celeste’s value (approximately £1,700, or about $8,300 at the time). This is sometimes interpreted as suggesting that the hearing could not completely dismiss Solicitor General Solly-Flood’s suspicions against the Dei Gratia’s crew. If their rescue had been deemed an entirely commendable act, a higher reward would typically have been paid.

However, the most crucial issue, the disappearance of the crew, could not be definitively concluded. The court did not entirely rule out the possibility of some “violent act” but could not identify its specific cause. In the end, why and how the crew suddenly vanished remained a mystery.

This ambiguous conclusion fueled further debate about the Mary Celeste mystery in later generations. The inability of the official investigation to provide answers only heightened public imagination, giving rise to numerous theories that continue to be recounted to this day.

Part 5: Major Theories and Their Examination Surrounding the Incident

The Mary Celeste mystery, due to its peculiarity, has given rise to a multitude of interpretations and speculations. Here, we will examine the main theories one by one, exploring their plausibility and limitations.

1. Pirate Attack Theory

This was one of the most prominent theories from the outset of the incident. While piracy was not entirely absent in the Atlantic at the time.

- Content: The Mary Celeste was attacked by pirates, and although the cargo was not taken, the entire crew was either killed or abducted. The damage to the bow rope and the mainmast was interpreted as evidence of a violent struggle.

- Examination and Counterarguments:

- Untouched Cargo and Valuables: The biggest weakness of this theory is that the ship’s valuables (captain’s sextant and watch, crew’s personal items) and the valuable alcohol cargo were left completely untouched. The primary goal of pirates is typically plunder, and it is highly illogical for them to attack a ship without taking any loot.

- Lack of Signs of Struggle: There were no clear bloodstains, bullet holes, or signs of a major struggle found on board. The “bloodstains” claimed by Solicitor General Solly-Flood at the Gibraltar hearing were later found to be rust or wine stains.

- Historical Context: At the time, large-scale piracy in the Atlantic had significantly decreased compared to earlier periods. Furthermore, the benefit of targeting a relatively small merchant ship like the Mary Celeste would have been limited.

- Conclusion: Due to the untouched cargo and personal belongings, and the absence of signs of struggle, the pirate attack theory is considered highly unlikely.

2. Mutiny or Murder by the Crew Theory

This grim theory, also proposed early on, suggests that the crew rebelled against the captain and killed everyone, or that internal conflict led to a mutual slaughter.

- Content: Dissatisfaction with Captain Briggs’ strict discipline or personal conflicts escalated, leading the crew to mutiny, kill Captain Briggs’ family and loyal crew members, and then escape in the lifeboat.

- Examination and Counterarguments:

- Captain’s Reputation: Captain Briggs was known as a highly respected and trustworthy individual, and his relationship with the crew was reportedly good. There was no clear motive for a mutiny.

- Crew Quality: The crew members were all experienced and steady individuals, with no record of causing trouble.

- Lack of Evidence: As mentioned, there were no signs of a major violent struggle, bloodstains, or weapons found on board. If a mutiny had occurred and led to killings, some evidence would surely remain.

- Unclear Objective: If they mutinied and took over the ship, why would they abandon it and escape into the rough sea in a lifeboat? Their subsequent objective remains unclear.

- Conclusion: Due to the lack of evidence and unclear motives, this theory is also not considered conclusive.

3. Insurance Fraud Theory

As suspected by Solicitor General Solly-Flood at the Gibraltar hearing, this theory suggests that the ship’s owners or Captain Briggs himself abandoned the ship to claim insurance money.

- Content: The owners of the Mary Celeste conspired to abandon the ship, making it appear sunk, in order to defraud the insurance company. To do so, the crew was secretly disembarked or killed.

- Examination and Counterarguments:

- Ship’s Condition: The ship was found largely intact and in a towable condition. If the intention was insurance fraud, the usual practice would be to completely sink the ship or damage it extensively to make it appear beyond recovery. Abandoning an intact ship to claim insurance would be too risky.

- Captain Briggs’ Character: Captain Briggs was known as a man of high integrity, and his character was far removed from someone who would engage in criminal acts. It is highly unlikely he would endanger his family for fraud.

- Fate of the Crew: If the crew were secretly disembarked, there is no explanation for what happened to them afterward, or why not a single one of them ever reappeared publicly.

- Conclusion: Based on the ship’s condition and the captain’s character, the insurance fraud theory is considered highly improbable.

4. Alcohol Gas Explosion (or Flash Fire) Theory

This is currently one of the most prominent theories, often considered from a scientific perspective.

- Content: The industrial alcohol cargo evaporated due to temperature changes or the ship’s motion, and the flammable gas filled the cargo hold. A small explosion (or flash fire) occurred, causing the crew to mistakenly believe the ship was about to explode and catch fire. In a panic, they quickly boarded the lifeboat. However, the rope connecting them to the ship either broke for some reason or was accidentally cut, causing them to drift too far from the ship and ultimately be swallowed by the Atlantic waves or carried far out to sea.

- Examination and Evidence:

- Cargo Properties: Denatured alcohol has a low flash point (around 13°C for ethanol) and is highly volatile. It is entirely plausible for gas to leak from barrels and accumulate in the cargo hold due to temperature fluctuations and the ship’s motion during the voyage.

- Lack of Major Explosion Damage: Against the counterargument that there was no evidence of a large-scale explosion on board, this theory is explained by the phenomenon of “deflagration.” This is a “rapid combustion” when flammable gas burns, producing a sound but without the destructive force to rupture the ship’s hull. It might have been a simple “flash fire” rather than an explosion. This would have caused the crew to feel their lives were in danger, and to hastily evacuate to escape the smoke and heat.

- Open Main Hatch: The open main hatch can be interpreted as a means of venting gas or expelling smoke after a flash fire.

- Missing Lifeboat: If they boarded the lifeboat in a panic, they would have had little time to prepare, explaining why they left without food or water. Even if they were tethered to the ship, the rope could have broken due to sudden waves or wind, or been accidentally cut in the panic.

- Captain’s Cautious Nature: Considering Captain Briggs’ highly cautious nature, even a small explosion or flash fire, given the alcohol cargo, might have led him to overestimate the risk of a full-blown explosion and fire, prompting him to order a temporary evacuation for the crew’s safety. This scenario is consistent with his character.

- Crew’s Absence: The fact that no ship searched for them while the Mary Celeste drifted, and they ultimately did not survive in the Atlantic, also aligns with this theory.

- Conclusion: This theory can explain the remaining physical evidence, scientific principles, and human psychological aspects relatively consistently, making it currently the most plausible theory. However, without definitive evidence (e.g., clearer signs of a gas flash), it remains a “hypothesis.”

5. Waterspout Theory

This theory suggests that a waterspout, which frequently occurs in the Atlantic, caused the crew to be thrown overboard or to evacuate in a panic.

- Content: The ship encountered a powerful waterspout during its voyage, which directly hit the vessel. This either swept the crew overboard or caused such violent pitching that the captain ordered a temporary evacuation. However, when they tried to return to the ship after the waterspout passed, they were separated from it by strong waves or currents.

- Examination and Counterarguments:

- Possibility of Occurrence: Waterspouts do occur in the Atlantic. They can appear suddenly and cause significant localized damage.

- Lack of Physical Evidence: If a waterspout had directly hit the ship, there should have been extensive damage to the hull, mast, and sails. However, the Mary Celeste’s damage was minor for a waterspout impact, and overall structural damage was not observed.

- Logbook Record: The last logbook entry recorded calm weather, with no mention of encountering a severe storm or waterspout. However, waterspouts can form suddenly and pass quickly, so it’s not impossible that there wasn’t time to record it.

- Conclusion: While possible, this theory is not considered strong due to its low consistency with the physical evidence.

6. Temporary Abandonment Due to Seasickness Theory (Peculiar Theory)

This is a relatively strange theory, but it has been mentioned by some.

- Content: Captain Briggs’ wife, Sarah, was suffering from severe seasickness, and to get fresh air, they temporarily lowered a lifeboat, tethered it to the ship, and went outside. At that point, for some reason, the rope broke, and they drifted away.

- Examination and Counterarguments:

- Contradiction with Captain’s Character: It is highly unlikely that an experienced captain like Briggs would order such a reckless and dangerous action as boarding an unstable lifeboat during a voyage, even for his wife. Especially considering his 2-year-old daughter was also on board, the risks would have been immeasurable.

- Crew’s Presence: There is no explanation as to why the entire crew would need to accompany them.

- Conclusion: Given the captain’s character and the consistency of the situation, this theory is highly improbable.

7. Dei Gratia Crew as Perpetrators Theory (Suspected at Gibraltar Hearing)

This theory was strongly suspected by Solicitor General Solly-Flood in Gibraltar.

- Content: Captain Johnson or the crew of the Dei Gratia murdered the Mary Celeste’s crew, seized the ship, and sought to claim a salvage award. Solly-Flood cited the “bloodstains” and strange damage on board as evidence.

- Examination and Counterarguments:

- Lack of Evidence: The “bloodstains” were later disproven, and there was no clear evidence of a violent struggle.

- Captain Johnson’s Reputation: Captain Johnson, like Captain Briggs, was a respected veteran sailor, and there was no apparent motive for him to attack a friend’s ship. Furthermore, the Dei Gratia’s crew remained calm after the incident and showed no suspicious behavior.

- Low Salvage Award: If they had committed such a crime, the salvage award received was too small to justify the risk.

- Conclusion: The court found insufficient evidence, and this theory is now largely discredited.

Part 6: Factors Deepening the Mystery and the Incident’s Cultural Impact

The Mary Celeste mystery continues to fascinate people and be recounted to this day due to a combination of factors. Moreover, this incident transcended the realm of a mere maritime accident, influencing numerous fictional works and becoming a cultural icon.

Factors Deepening the Mystery

- Contradictory Physical Evidence: The highly peculiar contradiction of a ship found largely intact, with cargo and valuables remaining, yet with all human life vanished, left ample room for various interpretations.

- Absence of a Clear Conclusion: The failure of the official Gibraltar hearing to provide a definitive answer to the crew’s disappearance fueled further speculation and debate. The fact that authorities could not solve it only heightened its mystique.

- Unresolved Fate: The fact that not a single crew member was ever found is the biggest reason why the mystery endures. If even one survivor had been found, the truth might have come to light.

- Media Frenzy: From the moment the incident occurred, newspapers sensationalized the inexplicable event. Much misinformation and exaggeration were included, which further deepened the mystery. In particular, Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story “J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement,” though fictional, was so realistic that many readers mistook it for fact, further popularizing the Mary Celeste story.

- Human Imagination: Humans tend to create narratives for unsolved mysteries. Even supernatural or science fiction interpretations, such as ghost ships, alien abductions, or sea monsters, emerged.

Literary and Cultural Influence

The story of the Mary Celeste has inspired many writers, filmmakers, and artists.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s “J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement”: As mentioned, this is the most famous fictional work based on the Mary Celeste incident. He depicted a grim story of revenge by a Black man and mass suicide on a deserted ship, based on prejudices of the time. Although fictional, this work significantly influenced the public’s perception of the incident.

- H.P. Lovecraft’s “Dagon”: The master of weird fiction, Lovecraft, also inspired by the Mary Celeste incident, included a passage in his short story “Dagon,” part of the Cthulhu Mythos, where the protagonist discovers a drifting ship and experiences strange events.

- Other Fiction: Jules Verne’s “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas” is also said to mention the Mary Celeste. Even today, the Mary Celeste is repeatedly featured in novels, films, television dramas, documentaries, and video games, becoming synonymous with unsolved mysteries, disappearances, and ghost ships.

The Mary Celeste is not just a maritime accident; it symbolizes humanity’s fear of the deep sea, awe of the unknown, and endless curiosity about unsolved mysteries. It will continue to be told as a part of human maritime history.

Part 7: Re-evaluation and New Perspectives in the Modern Era – Scientific Considerations and Erosion of Evidence

The mystery of the Mary Celeste continues to captivate people worldwide, even after more than 150 years. However, in the modern era, attempts are being made to re-evaluate it not merely as a mystery, but from a more scientific and rational perspective. New research methods, meteorological data, and oceanographic knowledge are shedding new light on this cold case.

New Meteorological Considerations: Microbursts and Squall Lines

While the traditional “waterspout theory” has been dismissed due to the lack of definitive damage to the hull, modern meteorological knowledge points to the possibility of more localized, yet extremely powerful, weather phenomena.

- Microbursts: These are powerful downdrafts from cumulonimbus clouds that hit the ground or water surface and spread outwards. They can cause sudden, localized gusts of wind, inflicting significant damage on small areas. If the Mary Celeste encountered a powerful microburst, the sudden gust could have caused the ship to list violently, throwing crew members overboard or causing them to panic and decide to abandon ship. As it’s a short-lived phenomenon, there might not have been time to record it in the logbook.

- Intense Squall Lines: It’s also possible that the ship encountered not a widespread storm, but a sudden and extremely intense squall line (similar to a linear rain band), which brought sudden gales and high waves. This scenario suggests the ship might have temporarily been in a dangerous situation, forcing a temporary evacuation in a lifeboat.

These meteorological phenomena could have caused powerful effects without structural damage to the hull, either forcing the crew to temporarily evacuate or sweeping them overboard.

Oceanographic Considerations: Currents and Drift Prediction

Attempts have been made to simulate the drift paths of the Mary Celeste and her lifeboat based on current oceanographic knowledge.

- Fate of the Lifeboat: If the crew left the ship in a lifeboat, their ultimate fate is the biggest question. By combining the towing path from the discovery site to Gibraltar with the prevailing North Atlantic current patterns of the time, it’s possible to estimate where the lifeboat might have drifted. If the lifeboat became separated from the ship and drifted with the currents, the chances of it being found in the vast Atlantic would have been extremely low. Given the lack of food and water, survival would have been hopeless.

- Ship’s Drift: The fact that the Mary Celeste herself drifted for about 10 days before being discovered by the Dei Gratia suggests that the wind and currents were relatively calm at the time. This also supports the alcohol gas explosion theory, implying that the weather was not necessarily at its worst when the crew abandoned ship.

Technical Perspective: Hull Design and Structure

The Mary Celeste was a wooden brigantine built in Canada, typical of ships of that era. However, she had experienced multiple groundings and collisions in the past and undergone extensive renovations.

- Potential Instability: It has been suggested that the lengthening of the hull during renovation might have affected the ship’s stability under certain conditions. However, Captain Briggs was experienced and should have been well aware of the ship’s characteristics.

- Material Degradation: It’s also possible that unseen material degradation had occurred due to years of use and repeated accidents. This could have led to unexpected minor hull distortions or gas leaks, for example.

These modern perspectives go beyond mere speculation, attempting to uncover the “truth” behind the incident using scientific data and simulations. However, without definitive evidence, these also remain within the realm of “hypotheses.”

Part 8: The Unconcluded Mystery, and Why It Endures

The story of the Mary Celeste remains unsolved, even after more than 150 years. Numerous theories have been proposed, and scientific analyses attempted, but the truth of why and how all 10 crew members suddenly vanished remains submerged in the depths of the sea.

Why the “Ghost Ship” Legend Continues

The Mary Celeste continues to captivate imaginations and be recounted for several fundamental reasons:

- The Ultimate Cold Case: An incident that remains unsolved, even with modern science, and for which no definitive evidence is found, continues to stimulate human curiosity. People tend to fill in unsolved mysteries with their own imaginations.

- Eerie Circumstances: The situation—an intact ship with ample food and water, and traces of daily life remaining, yet with all human life vanished—transcends our ordinary understanding. It evokes something supernatural, as if time had stopped or they were suddenly sucked into a dimensional rift.

- The Ocean’s Mystery and Terror: The ocean, vast and profound, has long inspired both awe and terror in humans. An inexplicable event in the middle of the sea embodies this mystery and terror, deeply imprinting itself on people’s minds. The fundamental recognition that uncontrollable forces exist in the sea, such as storms, sea monsters, or unknown entities, makes this story even more impactful.

- Fusion with Fiction: With many writers, including Arthur Conan Doyle, using the incident as a theme, the Mary Celeste’s story transcended mere historical fact to gain a life of its own in literature and entertainment. The extent to which fiction has deepened the mystery and cemented it in public memory is significant.

- The “What If” Question: The “what if” question—what would I have done if I were on that ship? What really happened?—sparks the imagination of readers and listeners.

Final Consideration: Convergence of Possibilities

Currently, the most plausible scenario is a combination of “alcohol gas deflagration (flash fire) in the cargo, panic-induced temporary evacuation, and subsequent separation and loss of the lifeboat.”

- On a calm sea, alcohol gas leaked from the cargo barrels due to some cause (e.g., ship’s motion or temperature changes) and filled the cargo hold.

- Suddenly, a small explosion (deflagration) or a flash of light from the instantaneous burning of the gas occurred. While not powerful enough to destroy the hull, it would have been a terrifying experience for the crew.

- Captain Briggs, concerned about the risk of the ship catching fire (especially with alcohol as cargo), prioritized the safety of his family and crew and ordered an emergency evacuation.

- The crew lowered the lifeboat and temporarily evacuated outside the ship while still tethered (supported by the open main hatch, missing lifeboat, and the chronometer and sextant being taken).

- However, immediately after, due to unforeseen circumstances (sudden wave, deteriorated rope, accidental cutting in panic, etc.), the rope connecting the lifeboat to the Mary Celeste broke.

- The Mary Celeste began to drift with the wind and currents, while the crew in the lifeboat were left isolated in the vast Atlantic, ultimately unable to survive.

This scenario can explain all the remaining physical evidence, the characters of the captain and crew, and the sea conditions at the time, relatively consistently. However, these are merely the “most probable” inferences, and without definitive corroboration, they cannot be declared as “the truth.”

The mystery of the Mary Celeste will likely remain unsolved forever, continuing to be told as part of humanity’s maritime lore. It will continue to pose many questions to us, serving as a symbol of the ocean’s vastness, nature’s power, and human curiosity about unexplained events.

Comments